Small-Animal VR Trackball

The development of the trackball was the second project in which I led the team and mentored junior engineers and scientists through the development process. We were able to successfully develop a working system, test to find issues and iterate to solve them, and ultimately perform a successful proof-of-concept study before transitioning the project to a junior team member when I graduated.

The Trackball VR system was developed to address two primary needs: first, a way to test the minimally-invasive preparation process under ambulatory (walking) conditions, and second, a method to obtain simultaneous neural- and behavioral-data.

Recording neural responses and behavior separately allows comparison of averaged responses, but prevents comparison of variances in trial behavior and neural activity. For instance, one behavioral assay in insects like drosophila or honeybees is the proboscis-extension response (PER), where a stimulus such as a smell is produced, and the animal responds by extending its proboscis to receive a reward or seek out food. However, on some trials the animal may not respond; was that because of a change in how the sensory stimulus was processed, or some other change in neural response? Without simultaneous recording, such comparisons are difficult or impossible to make. Being able to make those comparisons is an important tool for reverse-engineering how olfactory information is processed to identify odorants, localize sources, and drive behaviors such as PER or navigation.

Phase 1: Identification of ProblemA previous project to meet similar aims was a two-chamber wind-tunnel in which an ambulatory locust was tethered to an implanted electrode, and allowed to navigate a pair of small behavior chambers. However, while the design permitted simultaneous recording of neural and behavioral data, it had several key flaws.

- The long electrode tether introduced movement noise into the neural recording. This could be alleviated by mounting a small amplifier to the locust, but the additional weight interfered with behavior.

- Exposure to the stimulus and control sides of the chamber relied on the locust choosing to explore; if the locust only moved a small amount the trial might not yield useable data.

- When remaining on the side with the odorant, adaptation rapidly returned the firing to near baseline. Therefore the strongest responses with the most neural information were when the locust was crossing the midline, exacerbating the difficulties when locusts didn’t move a large amount.

The trackball system was intended to address these constraints, and better replicate a testing environment for the intended final stage of a cyborg locust sensor, with a miniaturized amplifier and digitizer system mounted on the back of the locust connected to a short implanted electrode.

Phase 2: PlanningThe second phase was to develop the requirements for the design so as to solve the problems listed earlier and optimize for future use, including:

- Ability to track the movement of the ball with a fairly high (~1000+ Hz) sample rate

- Video recording of locust behavior, e.g. antennal movements

- Multi-channel olfactometer

- Short electrode necessitates amplifier be mounted close to the locust

- GUI and task configuration files to ease use

- Stable and low-friction ball movement

- Simple and stable transfer of the locust from the surgical bed to the trackball

To meet these requirements several strategies were explored; adding visual patterning to the ball and tracking the movement using a webcam could provide accurate tracking, but would require use of an expensive high-speed camera, and would generate large amounts of data requiring much more preprocessing. Instead the use of two mouse sensors, positioned 90 degrees apart, was used to simplify tracking and provide sufficient sample rates.

In addition, I designed a modular system for streamlining the process of implantation and transfer to the trackball system, integrating the minimally-invasive surgical method to improve success rate and reduce preparation time.

Phase 3: Development and Initial ConstructionDevelopment proceeded on multiple components in parallel, divided into X modules:

- mouse sensor tracking system

- GUI, camera recording, embedded communication, data logging, and task file

- 8-Channel olfactometer

- Low-friction trackball

- Locust harness and mount system

Initially the team consisted of one undergraduate researcher, so we divided up the tasks between us. I handled initial development of the olfactometer, trackball, and harness and mount system, while he worked on mouse sensor communication and started the GUI development and feature incorporation.

Phase 4: Testing and Iteration

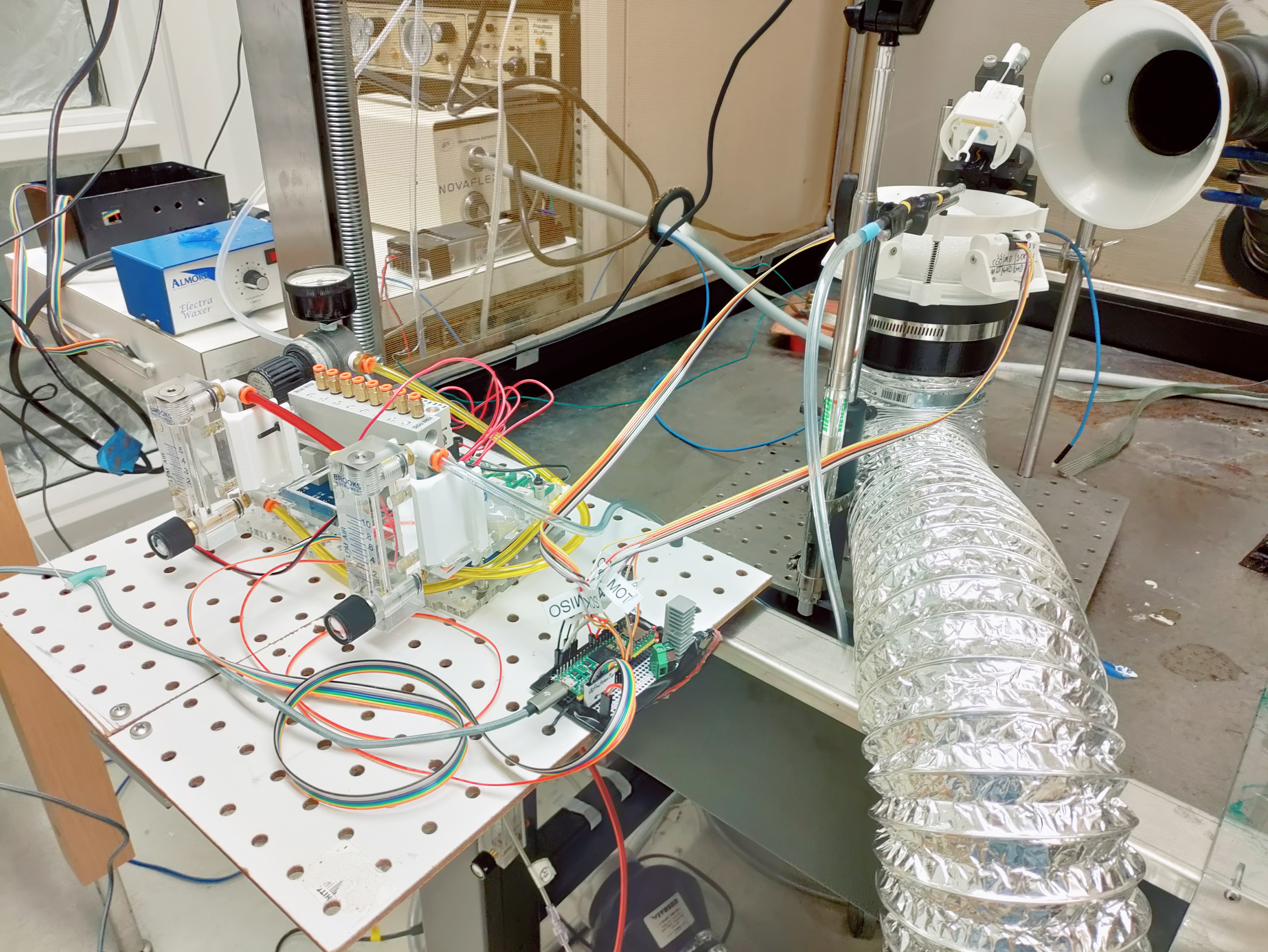

OlfactometerThe olfactometer was based off a reduced channel-count version of the 24-channel olfactometer developed earlier, and so was straightforward to assemble, and proved reliable in testing. Flow regulators were incorporated along with the solenoids and solid-state relay board into a unified module for simpler use.

In addition, I wrote a small embedded library for controlling stimulus timing, and enabling settings, run, and abort commands from the serial line for interfacing with the GUI.

The trackball presented a larger development challenge. A foam ball was selected for cheapness, ready availability, and the rough texture providing a better walking surface. Initial prototypes produced an air cushion using pressurized air, but while it did provide a low-friction support for the foam ball, however balancing presented challenges, and produced imbalanced forces causing movement of the ball, or when severe large oscillations. While not sufficient to force a locust to navigate a given direction, the force would bias behavior, introducing noise to the data. In addition, the release of the high-pressure air was quite loud and interfered with experiments being conducted in the same room.

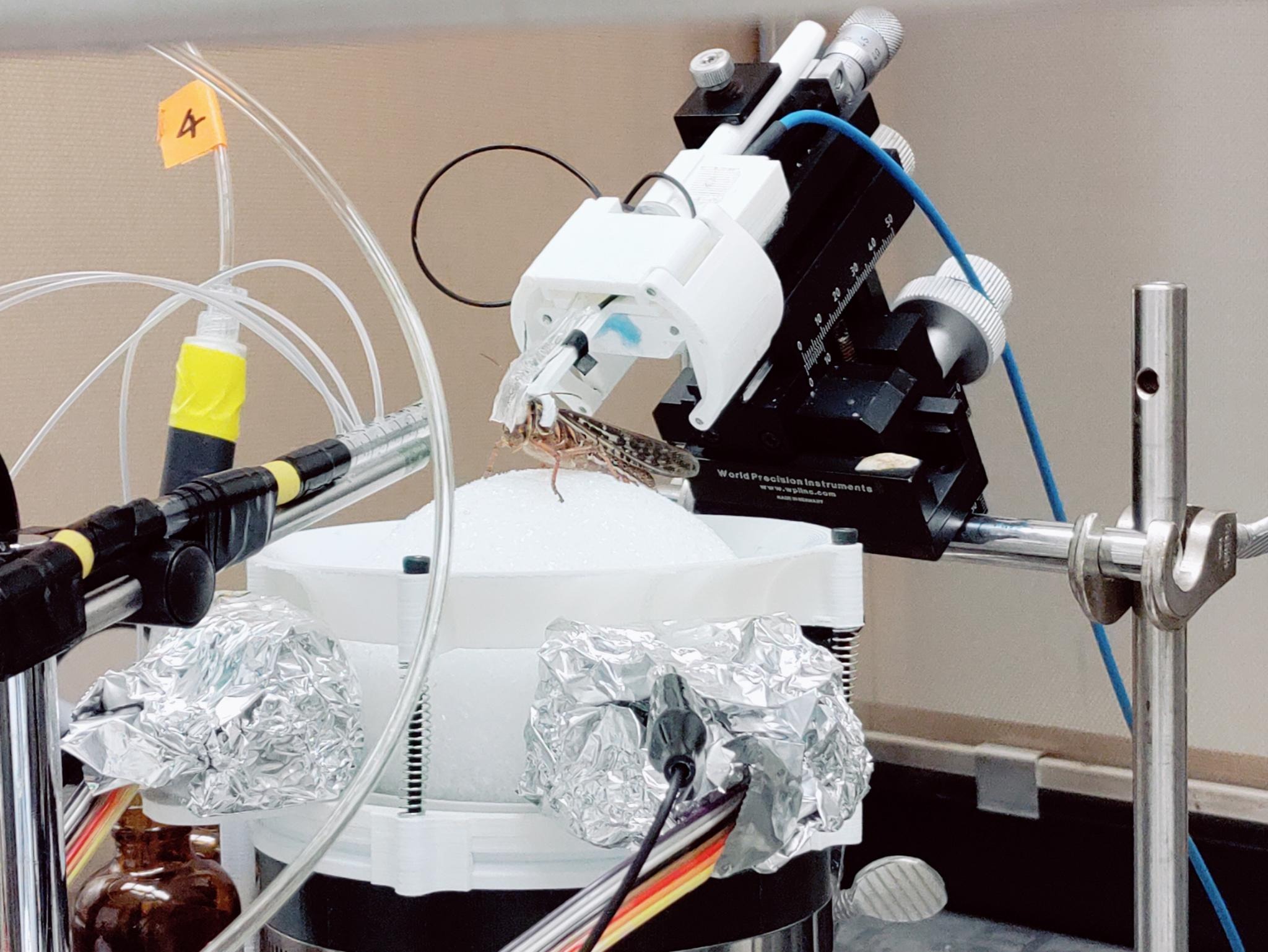

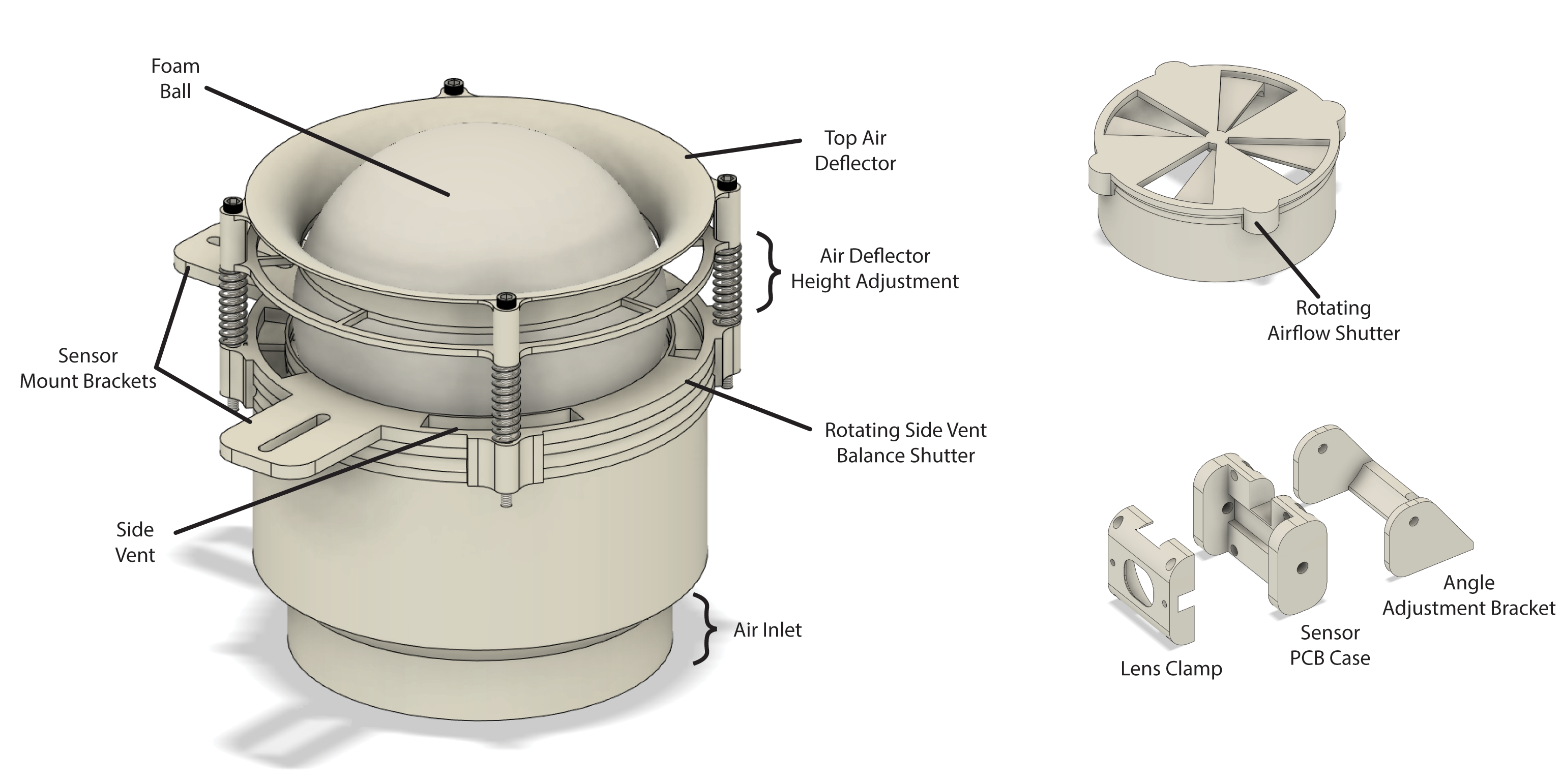

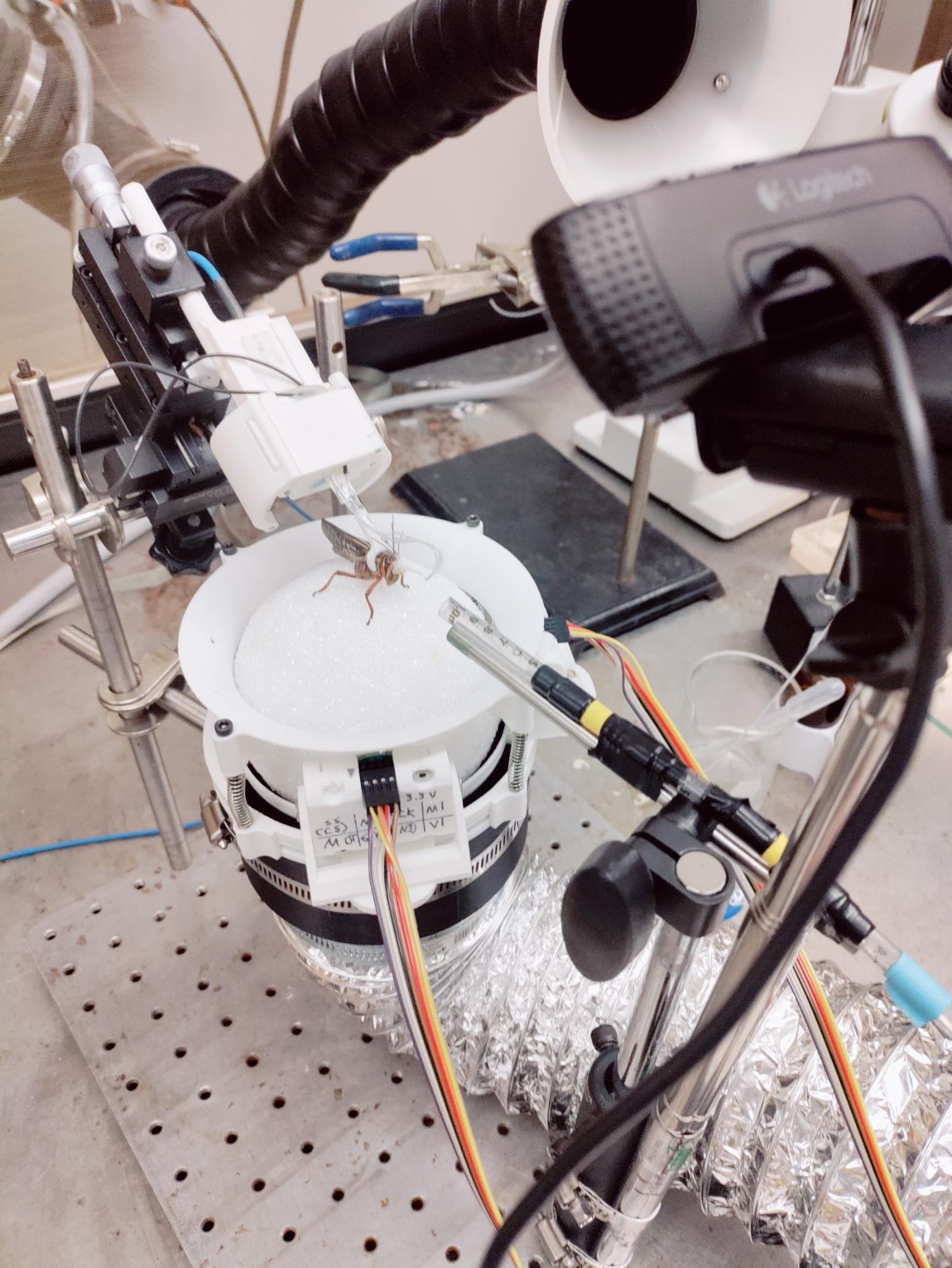

A better solution was found by suspending the ball on a low-velocity, high-volume air cushion provided by an inline fan, and routed through a perforated hemisphere in which the ball was suspended. Additional stability was provided by four vents on the rim of the hemisphere that released air-streams to the sides of the ball, constraining lateral movement. A rotating shutter mechanism allowed tuning of the aperture size of the vents, with the total air volume being modulated by fan speed or a second shutter positioned over the fan inlet. Mounting points for the mouse sensors were also incorporated along the equator of the foam ball. Testing revealed that the air cushion also caused significant turbulence above the foam ball where the locust would be. To prevent this from disrupting olfactory stimuli, a deflector was added, with height adjusted using four 3mm screws.

The design of a system for harnessing the locust, implanting the electrode, and easing transfer to the trackball system overlapped with the refinement of the minimally invasive surgical process. The details on this development are explored in the Implantation Surgery Tools and Processes project.

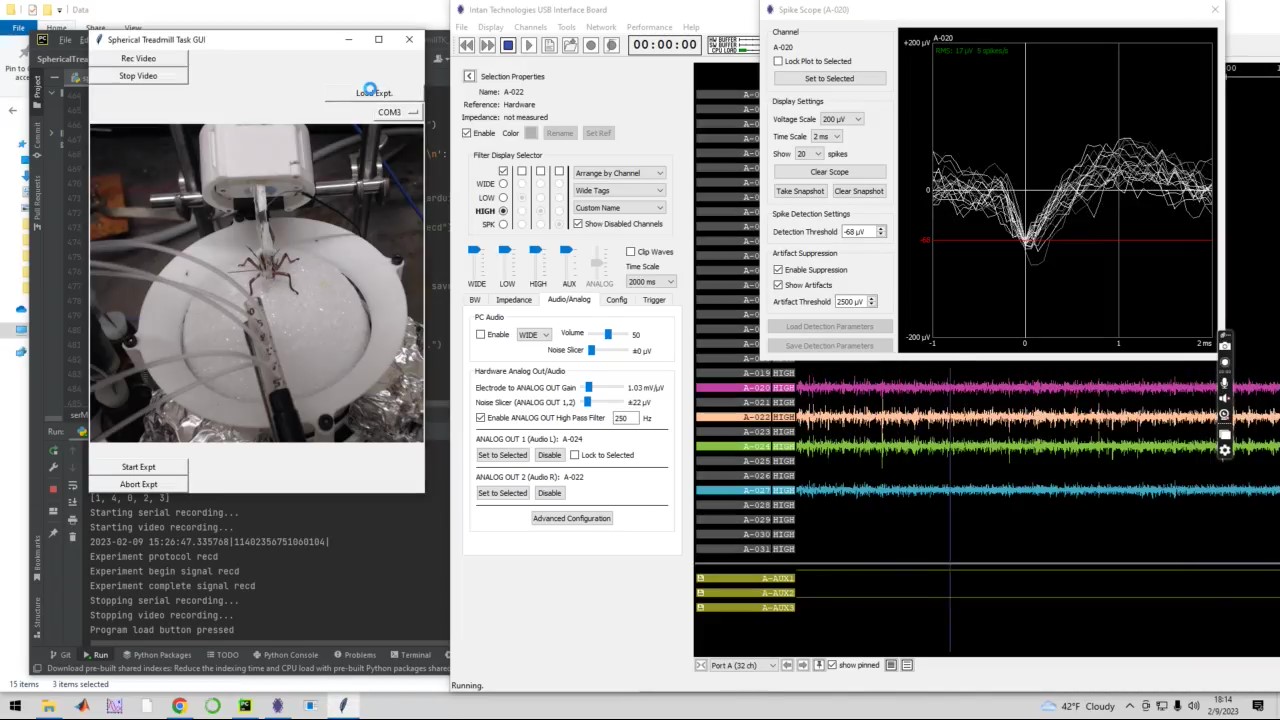

GUI

The undergraduate team member developed an excellent basic GUI, but during testing it was found that it was unstable due to the GUI framework being incompatible with multithreading. Unfortunately the undergraduate member graduated before having time to rework the code. To prevent IO operations from locking the code, I rewrote it to use multiple processes instead, with the GUI spawning two subprocesses, one for recording and timestamping video data, and one handling serial communication. I also added some features that hadn’t yet been incorporated, such as the ability to load task settings files for different experiments.

The project's initial sensor communication was spearheaded by the undergraduate team member. Following initial testing, the decision was made to upgrade from the ADNS-3050 to the more ADNS-9800 sensor both for better performance and the availability of a breakout board PCB. This transition also provided an opportunity for onboarding a new graduate-student team member, who was assigned to perform testing and update the code to use the new sensors.

I designed and assembling mounting cases and brackets for the sensors, and we were able to tune alignment and calibration. During this testing we also discovered that the activation of the sensors introduced electrical noise in the neural-recording system. This was solved by simply adding grounded shielding to the sensor cases.

Testing incorporated componentsOnce the individual components had been validated, the full system was assembled. Synchronization between different components was achieved through TTL pulses sent from the Teensy 3.5 microcontroller, which handled all task timing once the task protocol had been sent and the start-experiment signal received from the GUI.

At this point another member was added to the team, a graduate materials scientist who I had previously collaborated with in the development and testing of the flexible electrodes. We then engaged in testing the full system with live locusts, and through a series of revisions dramatically improved the success rate of the implantation surgery from around 20% to over 70%, and reduced the duration of the preparation time by ~80%. With the process at a satisfactory point and the remaining bugs stamped out, we proceeded to a proof of concept study.

For the proof-of-concept study, a small selection of odorants from the treadmill and other lab studies were assayed. Stimulation parameters were configured to match other previous experiments in the lab, and movement and neural responses to the stimuli were recorded across seven locust preparations. I analyzed movement data, and found that approach to one of the attractive odorants was positively correlated with the magnitude of the neural response to the stimulus, demonstrating the utility of the method for analyzing simultaneously recorded neural and behavioral data.

While further additions and revisions remained to be made (e.g. antennal tracking, fine-tuning and validating spike sorting, etc.) the project was sufficiently advanced for application to research and validation questions, and I was leaving for graduation soon. During the course of development the junior graduate student had been sufficiently trained and immersed in the project to be capable of taking over the project on my departure.